How the TinyGo playground simulates hardware

You may have seen the recently launched TinyGo playground. It works just like the Go playground, except that it also simulates real hardware in your browser like an e-paper display. There is no emulation like QEMU or Unicorn. There is no real hardware involved. So you might wonder, how does this magic work?

The trick is that in TinyGo, board support is separated from chip support for most boards. So you might compile for the Phytec reel board but target the WebAssembly instruction set as output. In this case, only pins and a few peripherals are defined, but this is enough for most programs.

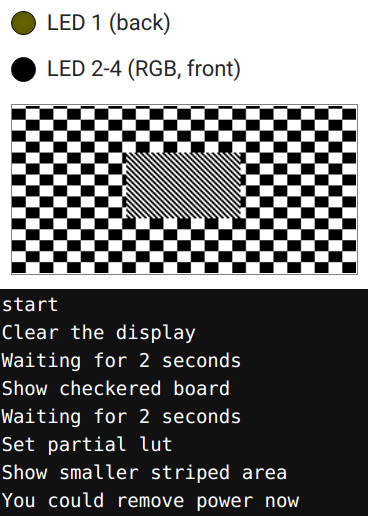

Let's take a look at how an e-paper display can be driven, as shown in this code of which you can see a screenshot above. The e-paper driver uses a few GPIO pins and a SPI peripheral. We'll take a look at the SPI peripheral simulation because it's more interesting.

The magic happens in a few places. One is the machine_generic.go file in the TinyGo machine package. It is built only when not targeting microcontrollers, as you can see in the build constraint at the top.

func (spi SPI) Configure(config SPIConfig) {

spiConfigure(spi.Bus, config.SCK, config.MOSI, config.MISO)

}

func (spi SPI) Transfer(w byte) (byte, error) {

return spiTransfer(spi.Bus, w), nil

}

//go:export __tinygo_spi_configure

func spiConfigure(bus uint8, sck Pin, mosi Pin, miso Pin)

//go:export __tinygo_spi_transfer

func spiTransfer(bus uint8, w uint8) uint8

What you can see here is that the spiConfigure function is not defined at all: it has no body. The //go:export is a special pragma (equivalent to //export) that gives this function a name (in this case __tinygo_spi_configure and __tinygo_spi_transfer) to avoid conflicts with other symbols. Undefined symbols are generally allowed in WebAssembly as long as you tell the linker to ignore them.

That gets the program to compile, but obviously there is something missing. Another piece of the puzzle is the definition in runner.js that sets up a virtual SPI peripheral in JavaScript and forwards communication to the correct simulated device, in this case an e-paper display. It knows that it must talk to this instance of the e-paper class, because:

- The configured board (in this case the reel board) has fixed pin numbers which are known by the playground and the playground connects the e-paper object to these pins.

- When the SPI peripheral is configured, it uses the port numbers that belong to the e-paper screen - whether it's the real screen or a simulated screen.

So for example, when one byte is written to the SPI port and read at the same time (because that's how SPI works), a method on the board object is called, which then looks at the devices connected to that pin, sees there is an e-paper screen connected, calls a special method on the e-paper screen to transfer the byte, and returns the returned byte from the e-paper back to the program. This way, the e-paper only has to interpret the stream of data coming the running program.

This means that the work of adding a device to the playground boils down to interpreting this stream of data (combined with some other information like the high/low state of pins) and react appropriately in the UI. For example, when the e-paper screen get the "update buffer" command it updates an in-memory (frame)buffer and when it gets the "draw screen" command it updates a <canvas> element with what is in the buffer. That's how a program that compiles to WebAssembly can still talk over SPI to an e-paper screen without changes to the driver.