Concise version vectors

In a previous blog post I've talked about a program I wrote, dtsync. Now I would like to explain a bit about the algorithm that it uses.

Synchronizing many different replicas (directories) is a difficult problem. It may not seem like that difficult, but I would want an algorithm with these parameters, where Nr is the number of replicas and Nf is the number of synchronized files, usually comparable across replicas (when they are frequently synchronized).

- Each replica has a storage memory complexity of Nf.

- It is only necessary to compare states of two replicas to synchronize them both.

The naive approach may have a storage memory complexity of Nf ×Nr, storing per file in a replica metadata about the file in each replica. When we carefully analyze the situation, it isn't necessary, but that will require a bit of theory.

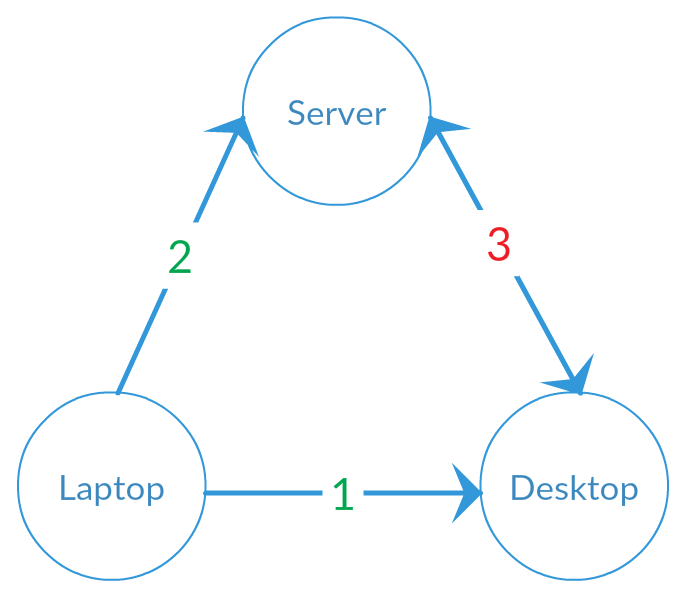

First the problem. Consider this scenario (see image below):

- A file is created on a laptop and then synchronized with a desktop computer, copying the file to the desktop.

- The file is modified and then a synchronization happens with a server, copying the modified file to the server. The laptop and the server now have the newer (modified) file, while the desktop still has the old version.

- A synchronization happens between the laptop and the server. From the point of view of this replica pair, both files are new. They don't have any state yet. Which one should be chosen by the algorithm?

A naive solution is simply to take the last modification time (mtime) of the file. But this doesn't work well in practice: modification time is a bad indicator of the actual modification time. Often, when copying files from other locations (cp -p), downloading files from the internet, or extracting files from a zip archive, modification time is something further in the past. And an overwritten file (appearing as modified) may thus have a modification time that's further behind than the "old" file. Additionally, some tools may accidentally update the modification time of a file without changing it's contents, thus making it appear newer than the other file while it might be older.

So we have to record each modification to each file, and have some way of communicating this information to the various replicas. The goal is always to know for single files (on one of the replicas) whether they are new on that side or deleted on the other, and for two files whether they differ, which one is updated, or whether they are both updated (resulting in a conflict). Keep this in mind.

Note that in file synchronization (or any kind of synchronization), we don't really need to know the actual times a file was modified. The only thing we need to know is when a file is modified, and which file is newer when you have two files from different replicas. This information is stored as a so-called version, which is simply a number starting at 0 and is incremented at each detected modification. Modifications can be detected using one-off syncs (a la rsync) or by continuously watching all files in the filesystem for changes (a la Dropbox). The counter never decrements, it only increments. This way, it is easy to compare two files for equality or which is bigger (newer).

Multiple replicas that can be synchronized in pairs with no particular structure, order, or reachability of other replicas. So in essence, DTSync is a distributed application, with a distributed algorithm. And what we're actually doing is modifying files, or in other words incrementing the version (and content) of that file.

One way to keep track of changes is using version vectors. The basic idea is simple. Each replica has a database with for each file a version vector. You can imagine it as a hashmap or Python dict object, for example {a: 2, b: 1, ...}, where a, b, etc are replicas and the numbers are the version (or last-modified counters). Version vectors and related terms are based in set theory, as brilliantly explained in this piece. On each modification, a new event with an unique name (the next number, e.g. a3) is added to the set. This name is usually the node name + the counter for that file on that node (starting at 0). So actually, in the above example, we have {a1, a2, b1}, and after the new event we have {a1, a2, a3, b1} (remember, sets don't store order). Version vectors simply make this notation a bit less clumsy by only storing the last version per node (or replica), like {a3, b1}. I will use this notation for the rest of the article.

How do we know which file was modified, then? Well, it's actually quite easy. Just use the standard set theory. Each replica contains a version vector for each file. And you can compare the two version vectors (or event sets) to know which is newer. See for example the table below. As a helper updated versions are shown in boldface. Remember that the only thing we're interested in is which file is newer. Whether it has increased 1, 5, or 100 versions does not actually matter.

| replica a | replica b | result? |

|---|---|---|

| {a2, b1} | {a2, b1} | files are equal |

| {a3, b1} | {a2, b1} | replica a has a newer file |

| {a2, b1} | {a2, b4} | replica b has a newer file |

| {a4, b1} | {a2, b2} | both replicas have an updated file - conflict! |

This neatly tracks which file is updated. It doesn't track this in a very efficient way, but we'll get to that later, that requires a bit more explaining.

But how are new/deleted files found? Well, realize that we're actually merging two trees on a sync. Each replica also has a version vector. It's own version is incremented each time an update is detected in the replica, in any of the files (or maybe at each scan, that it doesn't really matter). And when two replicas are merged, they also merge each others versions. So the version vector of a replica indicates which replica trees it has merged into it's own replica tree, in other words which versions it "contains". For example, if we have {a10, b20} and {a12, b15} this will get joined to {a12, b20}. When we view the vectors as just sets, it's a union: Ha + Hb. This will be the new version vector for each replica that incorporates all the changes from the other replica1.

The test whether a unique file (a file on only one side of the replica pair) is old is quite simple: simply check whether it is included in the other replica. When it's old and should be deleted is when the file's version vection is a subset of the other replica (Hfa ⊆ Hb where Hfa is the version vector set of a file on replica a). That is: when the other replica has all changes related to this file, but it is gone at that location, it is deleted. When it doesn't have all changes related to the file, it is a new file.

So now we have a working system. It can detect all changes: new/deleted files, unchanged files, updated files (and which file was updated), and conflicting files. But unfortunately it stores quite a lot of data per replica, namely the whole version vector for each file. That adds quite a lot of data per replica, up to one version number per file in the tree with each new replica added to the mesh. Even if this replica is never again used.

There is an algorithm that stores only one version number per file, which is much more efficient. It is written in a paper by Microsoft, called Concise version vectors in WinFS. It was originally written for the abandoned WinFS project, a potential hybrid between a file system and a relational database. One of it's features was peer-to-peer synchronization without central authority, for example between a laptop and a phone2 during a flight without internet connection. Of course, when you put every possible data type (including whole mailboxes) in a single database containing perhaps millions of items and try to synchronize it with another device, any bit of metadata is a lot of overhead. You have to find something else.

I'm not going to explain the whole algorithm in detail. Admittedly I don't really understand it myself. But I will try to explain how I made a (perhaps slightly different) algorithm myself for DTSync.

For DTSync, I'm using a random UUID generated per replica which is generated on the first scan. Additionally, I use a counter per replica that is incremented on each scan that detects changes. The state of each replica is then sent to the program that initiates the scan. That state is then compared to detect differences.

Using the theory from WinFS, there is a way to reduce store: simply don't store the whole version vector. Instead, store only the last version. That means only a single (replica ID, version counter) pair is needed. It is still possible to compare versions in a similar way. It even got a bit easier:

- To check whether a file is new or deleted, check whether the version of the file in the other replica. If it is, it already existed and is thus old and can be deleted. If it is not included in the version vector of the other replica, it was newly added and should thus be copied.

- To check whether a file is updated, check whether the file is in the other replica. This check can be done for both files. When only one of them is updated, that is a normal update. When both are updated it is a conflict.

With these changes, the storage space complexity has been greatly reduced. For each file only the name, hash, quickcheck metadata (mtime, size) and version are stored. A few lines from the metadata file that is saved:

| path | fingerprint | mode | hash | revision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dir | d/2017-03-20T17:06:09.849934621Z | 755 | 0:1 | |

| dir/photo.jpg | f/2015-11-27T20:07:01.376548679Z/188686 | 644 | V7RB[...]hU | 0:1 |

| dir/sub | d/2015-11-27T20:07:01.472548316Z | 755 | 1:2 | |

| dir/sub/fire.jpg | f/2015-11-27T20:07:01.476548301Z/3686 | 644 | siIQ[...]cQ | 1:2 |

| image.jpg | f/2015-11-14T14:33:45.872532224Z/188686 | 644 | V7RB[...]hU | 0:5 |

Here, you can see that I made a microformat for quick comparison of the metadata of two files: the filetype (d/f), mtime (ISO8601), and filesize (in bytes). I also added a hash to check whether files have actually changed or just the mtime got updated. And you'll see the revision column, which contains two numbers: replicaIndex:counter. The replicaIndex is a numeric index in a list of replica IDs, to save some more space.

In a future version, I want to save this file in a binary format, but a textual format is much easier for debugging purposes. Binary files can be much more compact (see e.g. the timestamp, the integers, and the base64-encoded hash). And perhaps more importantly: binary files can be much faster to parse: on a warm disk cache about ⅓ of the time scanning a big directory tree is spent parsing the textual tree state.

I hope you now understand a bit more of the algorithm behind DTSync. It took me a lot of effort to understand this algorithm without much CS background. And then it isn't easy to explain it in a clear way. I hope it is understandable.

-

When two replicas are not fully merged (for example when there are skipped files because of unresolved conflicts), they cannot join these sets. That's why not merging all changes in a sync can lead to false positives and merge conflicts. This means no data loss, just annoyance. ↩︎

-

Of course we're talking about the original Windows Mobile. Not to be confused with Windows Phone, which is a totally different system. Windows Mobile was more like Windows XP shrunk down to fit in a phone, including a horrible user interface and barely-working Internet Explorer (Opera was at the time the only browser that was actually usable on the device). This was my first 'smart' phone, the HTC Touch HD. ↩︎