Understanding modern mail authentication systems: SPF, DKIM and DMARC

Email. We use it every day. It's critical for most businesses and even though many alternative systems have been developed, it just refuses to die. At the same time, it's a very insecure and spam-prone system, as you will already know. To fix that, there has been quite some development work going on the last years to improve the situation regarding encryption and spam prevention. In a future blog post I will take a look at encryption but in this blog post I'm going to look at the latter: spam prevention, or rather, attributing email messages to sending domains so it gets easier to build reputation systems. When you know which messages are good, it's easier to drop the bad.

Email is a very complex system. It is very old (even older than the internet itself, having its roots in the ARPANET) and thus has accumulated a very large amount of cruft over the years. In addition to that, it has an extremely big installed base of possibly millions of hosts. But whether you like it or not, a large proportion of mailboxes are now in the hands of a handful providers (Google, Yahoo, Microsoft). This makes it a bit easier to change details of how the protocol works and to give initial momentum behind adoption of new protocols.

That's all nice and good, but what are we talking about anyway? What does an email message look like behind the scenes? Well, here follows a very simple example:

From: alice@example.org

To: bob@example.net

Subject: demo

This is a small demo to show how email works.

Alice

Yes, that's all there is to it. In practice, many more headers will be added and most email clients will use some sort of MIME messages so HTML email and attachments can be more easily used. And during the transfer to the destination (example.com) the mail systems will add a variety of headers, sometimes reordering them, fixing them, or even "fixing" the body part if they think it's broken. All of this is usually completely transparent to the actual users of the system.

Here is how the server at example.org will send the email message to the server at example.net. Note that in practice, mail servers will often not be located at the bare domain (e.g. example.net) but a subdomain (e.g. mail.example.net). This could even be a completely different host. The sending domain can look up the mail server for the receiving domain using the MX record on the receiving domain.

220 mail.example.net ESMTP HELO mx.example.org 250 mail.example.net MAIL FROM: <alice@example.org> 250 2.1.0 Ok RCPT TO: <bob@example.net> 250 2.1.5 Ok DATA 354 End data with <CR><LF>.<CR><LF> From: alice@example.org To: bob@example.net Subject: demo This is a small demo to show how email works. Alice . 250 2.0.0 Ok: queued as 766B0245619 QUIT 221 2.0.0 Bye

This is a whole SMTP session. It could have been done from a telnet session. In fact, it is based on telnet sessions I did to my own Postfix server and to Gmail to test it. The bold parts are the parts that I have typed in myself.

This is what such a message looks like once it arrives at it's destination:1

Return-Path: <alice@example.org>

Delivered-To: bob@example.net

Received: from mx.example.org (mx.example.org [192.0.0.1])

by mail.example.net (Postfix) with SMTP id 766B0245619

for <bob@example.net>; Wed, 10 Aug 2016 18:26:44 +0200 (CEST)

From: alice@example.org

To: bob@example.net

Subject: demo

Message-Id: <20160810162652.766B0245619@mx.example.org>

Date: Wed, 10 Aug 2016 18:26:44 +0200 (CEST)

This is a small demo to show how email works.

Alice

Various headers have been added. For us, the interesting headers are the Return-Path and the Received headers. The Received header is there mostly for diagnostic purposes. You can track the whole delivery chain with it from mail server to mail server (there can sometimes be a fairly large amount of mail servers). The Return-Path header contains the same address as the "MAIL FROM" command in the above SMTP session. This "MAIL FROM" or return-path is also known under some other names like "envelope-from". Why this header is important will soon become clear.

Note that even this is not a complete mail message. Modern mail servers add many more headers for verification purposes (that's what this blog post is about!). Also note the many bold parts in the newly added headers: these are taken from the HELO, MAIL FROM and RCPT TO commands in the above SMTP session. The Date and Message-Id could also have been generated by us, but they'll be added by the first full-fledged email server in the path anyway (probably our own mail sending server).

Something important to realize, is that there are actually two "from" addresses, as you might already have seen:

- The from address as sent during the SMTP session in the "MAIL FROM" command and later added to the message as the Return-Path header. I will call this header the envelope-from. It is also called the MailFrom, RFC5321.MailFrom or return path in other places (RFC5321 describes SMTP).

- The from address in the email message itself, in the "From:" header. I will call this header the header-from. It is also just called the From:, From or RFC5322.From header in other places (RFC5322 describes the email message format).

Something similar is true for the "to" address, but the to address is not very relevant for our discussion. It can still be faked, though, but has less of an effect (it mostly just looks strange).

Any parts that are bold in the above example can be faked by a spammer. And they will do it, to take advantage of the good reputation of large email servers (e.g. Gmail, or any large company). In the past, there was no way to prevent this sort of abuse, apart from a special agreement between a sender and a receiver. But special agreements don't scale, so there was a need for something better, to authenticate the sending domain.

SPF: Sender Policy Framework

The first of these systems is SPF. It's a very easy (but incomplete, as we'll see) mechanism to bind sending servers to domain names. In the past, there was no way to know whether a given mail server (with a given IP address) was actually allowed to send mail from that domain. So mail receivers based trust mostly on the reputation of IP addresses and content classification, which only worked in limited ways. IP addresses change, get in the hands of spammers and back in the hands of legitimate senders. And there can be many different IP addresses for any given domain.

Enter SPF. The basics of SPF are very simple, just add a TXT record similar to this to the domain:

example.org. TXT "v=spf1 ip4:192.0.0.1 ~all"

This essentially says "any mail coming from @example.org will be from 192.0.0.1, the rest is suspicious". The ending modifier ~all indicates a "softfail" as opposed to a "hardfail" (-all) so mail will not immediately be dropped, but will be treated with a lot more suspicion. This is very useful for spam filters. Of course, there's much more to the spec as this, as you can read at openspf.org.

To know the domain, SPF-adhering mailservers look at the envelope from address, and optionally at the HELO or EHLO address2. The end results are that the MAIL FROM command (envelope-from) is validated in the following transcript (green domain):

220 mail.example.net ESMTP

HELO mx.example.org

250 mail.example.net

MAIL FROM: <alice@example.org>

250 2.1.0 Ok

RCPT TO: <bob@example.net>

250 2.1.5 Ok

DATA

354 End data with <CR><LF>.<CR><LF>

From: alice@example.org

To: bob@example.net

Subject: demo

This is a small demo to show how email works.

Alice

.

250 2.0.0 Ok: queued as 766B0245619

QUIT

221 2.0.0 Bye

How does that actually help? Well, legitimate senders will generally use their own (correct) envelope-from header. When most email from example.org adheres to the SPF spec, a receiving mail server (example.net) can give a higher reputation to the domain as a whole. That means that these message can have relaxed spam checks, reducing false positives.

When all mail from example.org adheres to the spec, the administrator from example.org can even publish a policy indicating that all email from example.org must be sent through their mail server (-all), making sure all other mail gets dropped. Unfortunately, this doesn't provide that much value as the envelope-from is not generally displayed to users and spammers can use any domain with no SPF policy (even their own) circumventing the protections. And as they can put anything they want in the header-from (which is displayed to users) this doesn't help much against phishing. Still, this is a good first step and the value of SPF will become clear later in the part about DMARC.

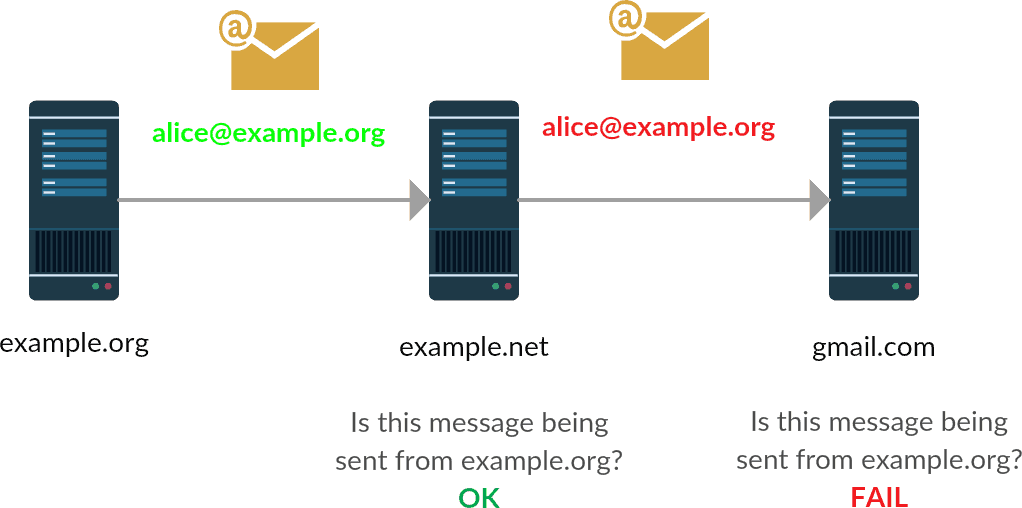

There are, however, a few problems with SPF. The main one is forwarding. Any time you forward email (not in the "Fwd:" sense, but on the mail server level), the envelope-from usually stays intact while the message was sent from a different mail server. The then receiving mail server will check the SPF information and finds it's being delivered by a different mail server than expected, so SPF fails while it's a legitimate message. See the following graph:

So we need something better. Something that doesn't break as easily, and something that actually protects the header-from that is visible to the user.

DKIM: DomainKey Identified Mail

DKIM (specified in RFC6376) takes a very different approach. It doesn't depend on IP addresses but instead signs many parts of the email itself. This makes sure authentication doesn't break with forwarding. The public key is stored in the DNS, something like this:

2016._domainkey.example.org. 299 IN TXT "k=rsa; p=MIIBIjANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQEFAAOCAQ8AMIIBCgKCAQEAviPGBk4ZB64UfSqWyAicdR7lodhytae+EYRQVtKDhM+1mXjEqRtP/pDT3sBhazkmA48n2k5NJUyMEoO8nc2r6sUA+/Dom5jRBZp6qDKJOwjJ5R/OpHamlRG+YRJQqR" "tqEgSiJWG7h7efGYWmh4URhFM9k9+rmG/CwCgwx7Et+c8OMlngaLl04/bPmfpjdEyLWyNimk761CX6KymzYiRDNz1MOJOJ7OzFaS4PFbVLn0m5mf0HVNtBpPwWuCNvaFVflUYxEyblbB6h/oWOPGbzoSgtRA47SHV53SwZjIsVpbq4LxUW9IxAEwYzGcSgZ4n5Q8X8TndowsDUzoccPFGhdwIDAQAB"

...That's a large amount of data. It's a 2048-bit RSA public key, in fact (one I stole from Gmail to give as an example). With this key, it's possible to sign various parts of the email message, using the DKIM-Signature header:

DKIM-Signature: v=1; a=rsa-sha256; c=relaxed/relaxed;

d=example.org; s=2016;

h=mime-version:from:date:message-id:subject:to;

bh=rr68DJxTrJcW1WD+Vx/gJvvzPjHsc7kRbbZc+jEtRuM=;

b=H3W0sqwJ7BjiYXxp/sNAgyaVmUSMlKmhpmx+Jr2Xw0BMoXopHFaEACapl/cbgUmNcc

IqJgYi1MbGFTZr+AOnpkBpu65fqTeTstLtK1mZvhCodMf1rVSOgI6a9FjXPQli9US222

MZATakL6nA3C1JOjqZabxgfItg4DIgITt8GDSnp2JxV4gjrJJH5zRD/R3E69bfDOAWz4

/Pd/gZEnM6BYK1N9g3mzhJ1e3S/RsD6OU1VTR9zGaIGuC2o/RloWbbm2BEbMNYk8VkGA

z1oHRVXG30hq1+7+VscrO14PzMp+gwDE0aau/WWplPjuw2zhZnx0S1YUMEzZ6R9TU9PY

aCPg==

From: alice@example.org

To: bob@example.net

Subject: demo

This is a small demo to show how email works.

Alice

You can see there are a variety of fields, most of which aren't that relevant for our example. The more important parts are the d key indicating the signing domain (I'll explain this later) and the h key indicating which headers are signed. The body is always signed by default. There is of course much more to it (the spec is very extensible) but these are the basics.

To verify a signature, a verifier takes the domain (d=) and selector (s=)3 and constructs a DNS TXT query:

selector._domainkey.domain

Then it can compute a hash of the body of the message, check it against the listed hash (bh=), and hash all the headers (including the DKIM-Signature header). This requires some trickery to avoid all kinds of issues with messages that get changed in legitimate ways on their way to their destination. I won't go into that as it's outside of the scope of this post and usually not required to understand anyway - the DKIM implementations will take care of that. Look into the "simple" and "relaxed" canonicalization algorithms if you're curious.

Determining the headers to include in the signature is configured by the sender, but which headers to include isn't very obvious. Section 5.4 of the RFC gives some guidelines to help people setting up DKIM signers. What might be important to know is that it's required by the spec to include the header-from and the DKIM-Singature header in the hash.

What's important to realize is that the DKIM signature in itself doesn't provide any form of trust. A message might as well contain a valid signature made by evil.com. The only thing a (valid) signature indicates, is that the signing domain takes responsibility for the message, in a similar way that SPF takes responsibility for valid SPF messages.

Another thing to realize is that there can be multiple DKIM signatures for one message, with different domains or different key+signature types. But it only makes sense to add a signature with the same domain as in the header-from address, so the header-from itself can be verified. This way, a verifier can know for sure a certain message was really sent by the indicated domain, even when it's forwarded to another mail server.

Here is how a SMTP session would look like using DKIM. Again, the green highlights are roughly the authenticated parts:

220 mail.example.net ESMTP HELO mx.example.org 250 mail.example.net MAIL FROM: <alice@example.org> 250 2.1.0 Ok RCPT TO: <bob@example.net> 250 2.1.5 Ok DATA 354 End data with <CR><LF>.<CR><LF> DKIM-Signature: v=1; a=rsa-sha256; c=relaxed/relaxed; d=example.org; s=2016; h=mime-version:from:date:message-id:subject:to; bh=rr68DJxTrJcW1WD+Vx/gJvvzPjHsc7kRbbZc+jEtRuM=; b=H3W0sqwJ7BjiYXxp/sNAgyaVmUSMlKmhpmx+Jr2Xw0BMoXopHFaEACapl/cbgUmNcc IqJgYi1MbGFTZr+AOnpkBpu65fqTeTstLtK1mZvhCodMf1rVSOgI6a9FjXPQli9US222 MZATakL6nA3C1JOjqZabxgfItg4DIgITt8GDSnp2JxV4gjrJJH5zRD/R3E69bfDOAWz4 /Pd/gZEnM6BYK1N9g3mzhJ1e3S/RsD6OU1VTR9zGaIGuC2o/RloWbbm2BEbMNYk8VkGA z1oHRVXG30hq1+7+VscrO14PzMp+gwDE0aau/WWplPjuw2zhZnx0S1YUMEzZ6R9TU9PY aCPg== From: alice@example.org To: bob@example.net Subject: demo This is a small demo to show how email works. Alice . 250 2.0.0 Ok: queued as 766B0245619 QUIT 221 2.0.0 Bye

DKIM also has some disadvantages, of course. The major ones are:

- Some mail servers rewrite parts of a mail message. This would normally be harmless, even helpful to fix broken messages. But it will break the signature.

- DKIM is a lot more complicated to set up. While for SPF you basically only have to publish a single line of text, for DKIM you have to generate a key, put it in the DNS, and configure all mail senders from your domain to sign messages using the DKIM signer. Also, the DKIM signer needs to be configured so it will know which keys belong to which domains and which messages it should sign.

As you might notice, the SPF and DKIM standards have exactly no overlap. SPF covers (just) the envelope-from domain name, and DKIM covers almost everything of the message except for the envelope. This means the standards could, in theory, work very well together, each verifying what they're good at and letting the other standard do the authenticating when the other stops working.

Just like SPF (-all), DKIM has a method of indicating the domain signs messages and that all non-signed messages must be dropped. But as this method (ADSP) was quite dangerous to use and never gained much adoption, it was deprecated. In practice, DMARC has replaced ADSP as a much more complete and generic method of determining authenticated messages and deciding what to do with unauthenticated messages.

DMARC: Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting & Conformance

DMARC takes both SPF and DKIM (or possibly both), makes them work together, publishes a clear policy of what to do with invalid messages, and it implements a reporting mechanism so senders know which messages get rejected. And some more things that I won't get into now.

Whew. That's a mouthful. Maybe I should do this more slowly. So, remember how our previous authentication methods work?

- SPF verifies the envelope-from domain. It only works on the first hop, but doesn't have problems with modified messages.

- DKIM verifies many things, including the header-from (which includes the header-from domain). It is not as robust as SPF to modification, but can be sent through many mail systems without losing it's authentication problems.

DMARC is built upon these two components, and ideally both have to be implemented for DMARC to work. But it can already be useful with only one of them, or even to some degree with none (for statistics).

A receiving mail server using DMARC will first verify SPF and DKIM. If none of them match, DMARC has failed. If at least one of them matches, there will be an "alignment check", or checking whether all hostnames match:

- For SPF, DMARC will check whether the verified domain name (from the envelope-from) matches the header-from domain.

- For DKIM, DMARC will check whether the given domain name (

d=in the DKIM-Signature) matches the header-from domain.

If at least one of them succeeds, the DMARC check has passed. Hooray! Now drink a beer after all this hard work. Or, if you're a mail server, continue with the next message that may already arrive within seconds.

This is the resulting header that's appended to the email message, after verification:4

Authentication-Results: mail.example.net;

dkim=pass header.i=@example.org header.s=2016 header.b=H3W0sqwJ;

spf=pass (example.net: domain of alice@example.org designates 192.0.0.1 as permitted sender) smtp.mailfrom=alice@example.org;

dmarc=pass (p=QUARANTINE sp=REJECT dis=NONE) header.from=example.org

This header can be very useful to determine whether all three systems work well, and I think is used in ARC, which I haven't investigated yet.

When a mail receiver has verified DMARC, it's time to decide what to do with the message. There are three policies, that can be specified by the sender (in the _dmarc TXT record):

- p=none: do nothing special with the message

- p=quarantine: put the messages in the spam/junk folder

- p=reject: drop the message immediately as spam/phishing

As you might imagine, senders like PayPal quickly adopted p=reject, as their domain is a frequent target for phishing:

_dmarc.paypal.com. 287 IN TXT "v=DMARC1; p=reject; rua=mailto:d@rua.agari.com; ruf=mailto:dk@bounce.paypal.com,mailto:d@ruf.agari.com"

Other domains take a more conservative approach, but some large scale providers (Yahoo, AOL) have already moved to p=reject. Gmail promised to move to p=reject in 2016, then in 2017, but it still hasn't changed anything. Their policy is still "none".

What you do for your own domain is of course up to you, but consider that moving to p=reject may be a bad idea. I personally use p=quarantine as I've seen a few messages getting lost otherwise, and it's wise to start with p=none anyway to monitor how well it works.

That brings me to the next part of DMARC: reporting. With the rua= and ruf= parameters, you can request aggregate and forensic reports (statistics and individual messages) that weren't validated. Note that while the rua= field is widely implemented, the ruf= field isn't because it's a potential privacy violation. You also might not want to use ruf= anyway because it will give a lot of messages.

I personally use dmarcanalyzer.com to analyze my mail messages. I have set it up in such a way that it sends mail to dmarc-rua on my domain, but forwards it to dmarcanalyzer.com. Their website works really well to get insight in how well a domain behaves, but of course you can try other providers.

Conclusion

Even a very old protocol like email is still being developed. We just can't live without it. Email is everywhere, so we have to make sure it keeps working. With these developments, I hope that spam will be reduced (although never fully eliminated) and phishing will be detectable and thus harder to pull off.

In a future post I'll take a look at recent developments in STARTTLS, or how to make sure encryption is not just optional (and thus easily stripped) but required. And why it's very hard to enforce encryption in email, unlike HTTPS.

-

I heavily edited this message to remove my own domains/address for spam prevention reasons and to hopefully make things a bit clearer, so I might have introduced errors. ↩︎

-

Using the envelope-from domain name is required, and using the HELO domain is recommended. If there is no envelope-from (as is the case in bounce/non-deliverable email), the envelope-from will be constructed from "postmaster@" + the HELO domain. As may become clear in the DMARC section, validating the HELO domain is not very relevant anymore (apart from bounce email). ↩︎

-

Selectors make it possible to add more than one public key to a domain. This makes key rollover possible (add a key, change the DKIM config, remove the key a week later) and makes it possible to gradually roll out support for a new algorithm in case rsa-sha256 turns out to be insecure. ↩︎

-

Again, I've edited/faked this header so there could be mistakes. ↩︎