Enforced STARTTLS for SMTP

Traditionally, SMTP has been completely insecure. Transported in plain text, with no authentication whatsoever. Luckily, the plain text part changed in RFC2487, later updated as RFC3207. It introduced TLS encryption for SMTP, but unfortunately no authentication. This means that passive eavesdropping becomes impossible (if both sides implement STARTTLS) but active eavesdropping (MITM) is still possible (albeit a bit easier to detect).

In recent years, there has been a big push to adopt STARTTLS, in part by companies like Facebook and Google. So the base for truly secure mail is being laid. But full encryption is only reached when there is a way to verify that the server you're talking to actually belongs to the target domain.

Unfortunately, enforcing a secure connection is a much more difficult problem in email than in HTTP. With HTTP, whether a URL is protected by TLS is encoded in the protocol prefix: http or https. A web browser knows when it should be talking to a secured and authenticated host and will bark when it doesn't. For email, there is no such thing: email addresses don't encode whether the target domain uses strict TLS. Additionally, email has a complication in that the domain doesn't receive the email itself, but points to one or more other domains (via the MX or Mail eXchange record) that receive the email. And this MX record lookup is by default not secured at all - like all of DNS (unless done via DNSSEC). A single mail server can receive mail from lots, lots of domains. For example, G Suite (formely Google Apps) can add email to a custom domain which is then managed by Google. This means the mailservers from Google receive email destined to lots of domains. There are many other mail and hosting providers that work in a similar fashion, providing a mail server for many customers.

So, when delivering mail, there are two indirections which both need to be secured:

- The MX record lookup using DNS is not secure by default, so can be tampered with - pointing to a different MX hostname.

- The mail server address (listed in the MX record) usually uses the MX hostname as the domain name in the certificate, as there are too many domains which can point to a given MX (e.g. G Suite).

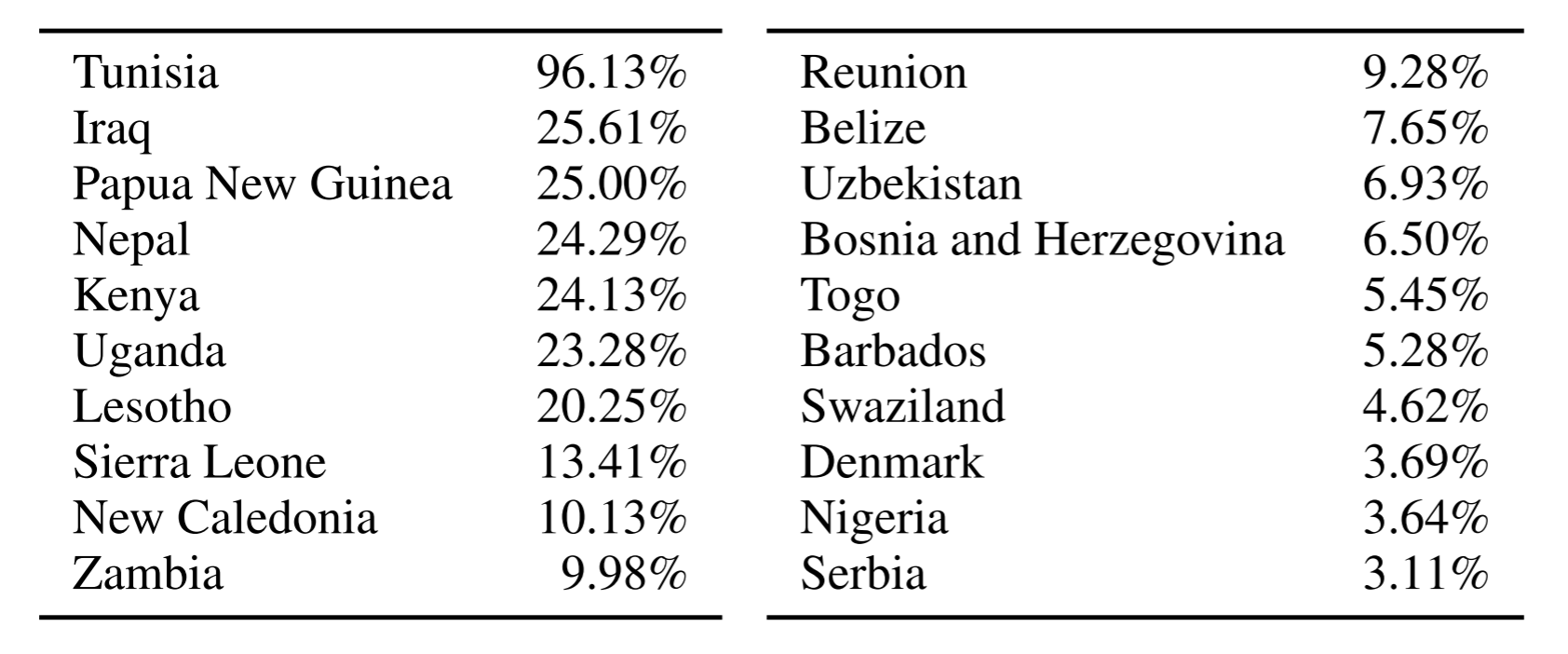

So why go through all the effort to enforce authenticated encryption? Because email is intercepted (MITM) on a large scale. As you can see below, this is usually done in not-so-democratic countries, but I wouldn't rely on the current Western governments to not spy on us with the current political climate.

(STARTTLS stripping by country, source: Durumeric et al.)

(STARTTLS stripping by country, source: Durumeric et al.)

There are currently two proposals to fix this situation: DANE and MTA-STS.

DANE for SMTP

The first approach is based on DNSSEC and DANE (RFC7672).

It works by building a chain of trust from the domain in the email address to the certificate presented in STARTTLS:

- The MX record lookup is authenticated via standard DNSSEC.

- The certificate of the mail server is verified using a TLSA record on the mail server domain.

The reason it is possible to build a downgrade-resistant system this way is because DNSSEC provides authenticated denial of existence. A domain which doesn't implement DNSSEC or DANE is left alone, but mail will be delayed when a domain implements DNSSEC and DANE but makes a mistake - or someone is tampering with the connection.

While using DANE for SMTP may seem simple at first, there are a lot of practical problems with it. For example, DNSSEC still uses a lot of obsolete cryptography like 1024-bit RSA. And of course, DNSSEC (required for DANE) is far from broadly implemented so many domains may not even be able to use it.

If you're already using DNSSEC setting up DANE for SMTP is quite easy. This is how I would recommend to configure it:

-

Make sure the domain with MX records (as listed in the email address) is secured using DNSSEC.

-

Make sure all mail server domains (the MX domains) are secured using DNSSEC.

-

Make sure the mail servers are configured for STARTTLS with a valid certificate (with the MX domain listed in the certificate).

-

Add a TLSA record to the MX hostname, like the following for Let's Encrypt:

_25._tcp.mx1.example.net. 86400 IN TLSA 2 1 1 60b87575447dcba2a36b7d11ac09fb24a9db406fee12d2cc90180517616e8a18

See [this forum post](https://community.letsencrypt.org/t/please-avoid-3-0-1-and-3-0-2-dane-tlsa-records-with-le-certificates/7022) for the rationale behind this configuration.

MTA-STS

Strict Transport Security for SMTP (MTA-STS, work-in-progress) uses a radically different approach. It doesn't rely on DNSSEC, but instead relies on the Certificate Authority system and trust on first use.

I will hopefully write a future blog post about how it exactly works, but the basics is relatively simple. A sending mail server determines whether MTA-STS is in use by fetching a special TXT record (just like DKIM, SPF and the like) and requests a policy file from the destination mail server. This policy has a max age that should be very long, but is often refreshed long before that time just in case (and can be refreshed manually by the destination domain by updating the TXT record). When it connects to the destination mail server, it checks whether at least one hostname listed in the TLS certificate is also listed in the policy file.

Trust is thus established by fetching a file from a special URL (on a subdomain of the destination host) and validating the TLS certificate against this file. And after the MTA-STS policy takes effect, it is impossible for an attacker to block it unless it somehow manages to block refresh attempts for the duration the policy is in effect.

To set up MTA-STS on your own domain, I've included some instructions over here. This is a tool to validate MTA-STS configuration, but includes some notes how to configure it on your own domain. Note that the spec still isn't finished, so unless you intend to keep an eye on future developments, I would recommend not to implement it on your domain.

Conclusion

While mail has traditionally been very insecure (but somehow managed to survive over all those years), the last few years have seen some development to make it more secure. Truly downgrade-resistant mail is still something that's a bit off, but now the groundwork has been laid or is being laid to make it happen. It will be some time before before this starts taking effect, though.

Also check out my other post about email authentication, which explains various relatively new (but already implemented) techniques to bind email to sending domains, making it easier to identify spam and phishing.