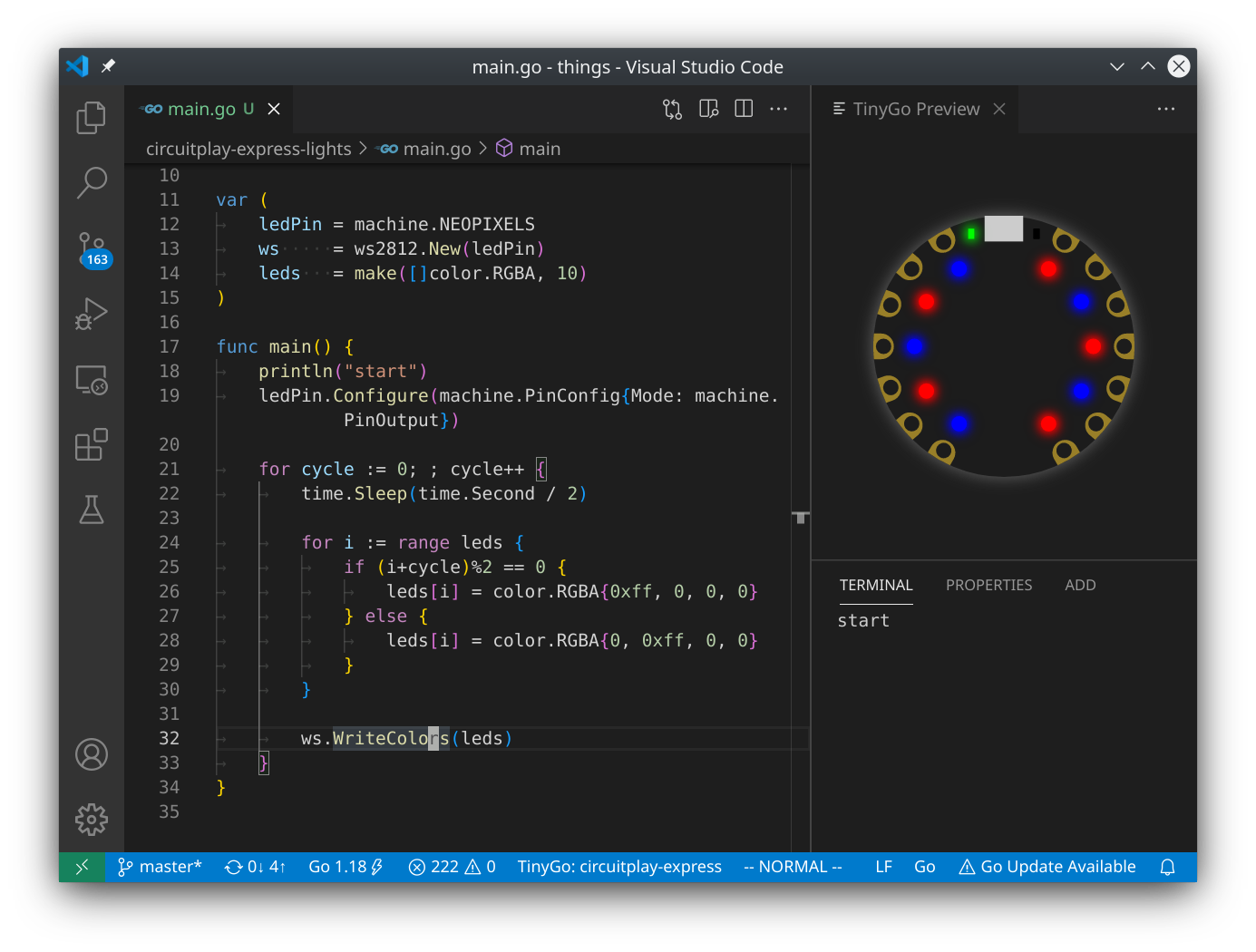

TinyGo Preview - how does it work?

The TinyGo Playground can simulate actual development boards inside a web browser. This has been true for a while, but since I last wrote about it, it has gotten a big overhaul. And since today, it is also supported in the VS Code extension. So how does it work behind the scenes?

The main idea has stayed the same, but a few important things have changed. Most importantly, it is now more stable, looks way better, and is more secure. Oh, and it is supported right inside VS Code!

Behind the scenes

Unlike the previous iteration, this version of the playground now splits the UI and the running of the code. The UI is done in SVG (hence the nice graphics!) and the code is running inside a Web Worker (or a Node.js Worker). Inside this worker, the code runs as a WebAssembly module.

To produce a runnable WebAssembly module that simulates an actual board, the playground compiles a binary with a command like this:

tinygo build -tags=circuitplay_express -opt=1 -no-debug -o=/tmp/path/to/module.wasm

Importantly, this produces a WebAssembly binary with the circuitplay_express tag set. The TinyGo machine package supports this, and has a special board_circuitplay_express.go file that is carefully written to expose all board constants (like machine.LED and machine.NEOPIXELS) but without depending on any details of the underlying chip (the ATSAMD21G18A in this case). This makes it possible to use pin constants from the machine package.

The machine package also implements things like Pin.Set for WebAssembly which calls a special __tinygo_gpio_set function instead of trying to access the hardware directly. This __tinygo_gpio_set function is then implemented on the JavaScript side and exported to the WebAssembly module. The web worker (written in JavaScript) tracks all the pin states and communicates this with the frontend.

And here is another change from how the playground used to work. Previously, a pin on a board was directly connected to a piece of simulated hardware, such as an LED. This is simple to implement, but not very flexible. The new version can actually simulate some pieces of hardware with wires between them:

In this case, I've simplified things and allow LEDs with just one side connected, the other side is assumed to be connected to VCC/GND as appropriate. And of course no resistors are necessary in a simple simulation!

How this works is that the UI sends the current state of the various devices in the schematic (board, LEDs, wires, etc) to the worker and the worker builds a netlist, which is a set of all pins that are connected together by wire. It then calculates the state of the netlist as a whole (floating, high, low, pulled high, pulled low) and updates all connected devices with this information. For example, if the simulated microcontroller sets pin D12 to high and this pin is connected via wire to the anode of a LED, the LED will turn on.

All of the logic behind the schematic is running inside the worker. That includes of course the microcontroller WebAssembly module itself, but also the logic for LEDs and other devices. The objects in the worker are all running synchronously and are sending messages to the UI whenever something changes (such as the on/off state of a LED, the color of a WS2812 LED, or the contents of a SPI display). The only thing the UI does is display the results inside the SVG. For example, to update the color of LEDs, the LED object in the worker sends a few CSS custom properties to the frontend which the frontend inserts in the SVG DOM. Display updates are communicated by sending a raw image buffer to the frontend which is displayed in a <canvas> element inside the SVG.

Security

With this approach, I think I've also made the system more secure. While there is currently no untrusted code running inside the playground, I might add such a feature to play.tinygo.org. And people might not expect code running inside the VS Code preview feature to have access to the filesystem, for example. I've encapsulated the system in a few ways:

- The WebAssembly module has very little access to the outside world. It can only call the functions it has access to.

- By running in a worker, the WebAssembly module cannot block the UI thread. This is not just bad for UI responsiveness, it can also result in a kind of DoS if someone (accidentally) writes an endless for loop. Whenever the code changes, this worker is simply killed and a new one is started with the new code.

- By using a Content Security Policy, any code that does escape from the sandbox doesn't have much access outside of it. This is especially important for VSCode where escaping from the sandbox could mean direct access to the host system (with file access).

Portability

With the playground now working in two different environments (in the browser and in VSCode itself), I'm pretty sure that it can be ported to other IDEs if necessary. The main requirement is a browser-like environment.

I've also thought of possibly supporting other languages. There is no fundamental reason why this isn't possible: the main requirement is for other languages to be able to compile to WebAssembly while still supporting platform constants such as pin numbers. The playground itself has a few TinyGo specific parts but the vast majority is language independent. Who knows, maybe we'll see Rust or a port of the Arduino core some day? Or maybe even MicroPython, Blocks, or others?

Conclusion

The new playground is a lot more powerful and looks a lot better than before. It is also a lot more extensible and should make it easy to develop firmware by directly integrating in the IDE.

My hope is that people will find it useful and will maybe contribute to it by adding more boards, more devices, and generally make it more powerful. For example, I'd like to add the following features some day:

- PWM support, and actually blinking or dimming LEDs as necessary.

- A kind of logic analyzer, built directly into the simulator. That way, you could get some experience with how a real logic analyzer works. This would of course include real waveforms, including those emitted by SPI and PWM.

- The ability to save and load schematics in VS Code, perhaps allowing them to be checked in to version control.

- The ability to share code snippets including full schematic on play.tinygo.org, similar to go.dev/play and godbolt.org. This is somewhat difficult because it is a much bigger surface for abuse and privacy leaks, so I'm not entirely sure how to do that in a way that I don't have to pay attention to all the time.

- Lots of small UX improvements and bug fixes, such as showing pin names when hovering over them.

Also I should mention Microsoft MakeCode, which was a big inspiration to the new playground. Although the underlying technology is very different, the user experience is intentionally similar. I think it's a great idea to lower the bar to embedded software development and let people experiment more freely without the risk of destroying any hardware during experimentation. And for more experienced people, I hope the preview feature in VS Code will improve productivity by directly seeing the effect of small code changes.